The Discovery Doctrine

The Christian ideology that has powered Western settler-colonialism for over 500 years

Just last week we were in Spain for a holiday, and while in Madrid we went on a tour to Toledo, in Castilla–La Mancha. One of our co-passengers in the bus was an American, who struck up a conversation with us as we were being led by the tour guide through the town and the magnificent 13th century Gothic cathedral. In the course of our sidebar chats he referred to something he called the “Doctrine of Discovery”. I had never come across that term before, so I asked him about it and then looked it up on my phone. I was intrigued enough by what I saw at first glance, to bookmark it for further study. When I got back home, and managed to catch up with my email backlog, I dove into it. I was quite fascinated by the whole thing, and particularly struck by the clarity with which I could now see a major part of world history in the appropriate light.

This brief essay is really a short desktop research note on the subject, with a focus on American jurisprudence and how it has been influenced by the mindset undergirding this doctrine.

Origins

The Discovery Doctrine emerged in the 15th and 16th centuries as European powers sought legal frameworks to justify their colonial expansion during the Age of Discovery. This legal principle established the norm that when European explorers “discovered” lands previously unknown to Europeans, they and their sovereigns gained special rights over those territories, overriding those of the indigenous inhabitants. The doctrine was born out of pragmatic needs: European powers required a system to resolve competing claims among themselves while providing legal cover for territorial acquisition.

The concept can be traced to papal bulls issued in the 1400s, particularly Pope Nicholas V’s Dum Diversas (1452) and Pope Alexander VI's Inter Caetera (1493). The latter divided the “New World” between Spain and Portugal, granting them exclusive rights to colonize specific regions. This framework evolved into a legal principle that European powers would later adopt and adapt to serve their colonial ambitions.

Following Christopher Columbus’ landing on the shores of the West Indies in 1492, Spanish conquistadores began building a colonial empire in the Americas. Hernán Cortés led the conquest of the Aztec Empire. From there, conquistadores expanded Spanish rule to northern Central America and parts of present day southern and western United States. Other conquistadores took over the Inca Empire after sailing to northern Peru. Subsequently, other conquistadores used Peru as a base for conquering much of Ecuador and Chile.

The doctrine’s need arose from the intersection of economic, political, and religious motivations. Economically, European powers sought new resources and trade routes; politically, they competed for global influence; and religiously, they pursued missionary objectives. The Discovery Doctrine provided a convenient legal structure that addressed all three needs while establishing rules of engagement among competing European powers.

The Church as an Enabler of Occupation, Slavery and White Supremacy

The Christian Church played an instrumental role in developing and legitimizing the Discovery Doctrine. The aforementioned papal bulls explicitly granted Christian monarchs divine authority to discover and claim non-Christian lands. Pope Nicholas V’s Dum Diversas authorized Portugal “to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans” and to place them into “perpetual slavery.” (Emphasis mine.) This religious framework established a hierarchical worldview that positioned Christian European societies above non-Christian, Indigenous peoples.

The doctrine was built upon the concept of terra nullius (“nobody’s land”) - the idea that lands not governed according to European Christian systems of government were effectively “empty” despite being populated by Indigenous peoples. This concept relied on a theological justification: non-Christians were considered not to have the same divine right to land as Christians. By classifying Indigenous lands as spiritually and legally “vacant,” the Church provided theological cover for colonization.

This religious dimension transformed colonization into a spiritual mission. The “civilization” and conversion of Indigenous peoples became a moral imperative that masked the economic and political motives of colonial expansion. The Church thus became not merely a participant in colonization but a fundamental architect of the intellectual framework that enabled settler colonialism to proceed with perceived moral authority.

Influence on Early American Settlers

The Discovery Doctrine profoundly influenced early American settlers and the founding of the United States. English colonists brought with them the European legal traditions that incorporated the doctrine, applying these principles to their relationships with Native American nations. Even as the colonies sought independence from Britain, they maintained this aspect of European legal thought.

In 1792, US Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson claimed that the doctrine of discovery was international law which was applicable to the new United States government as well. Thomas Jefferson, despite his ideals about natural rights and liberty, embodied the contradictions inherent in American application of the Discovery Doctrine. As the author of the Declaration of Independence who wrote that “all men are created equal,” Jefferson simultaneously pursued policies of westward expansion that relied on the doctrine’s premise of European superiority.

As president, Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase of 1803 exemplified how the Discovery Doctrine had been fully incorporated into American legal thinking. The transaction occurred between the United States and France with no consultation of the Indigenous nations who inhabited the territory. Jefferson’s vision of an “empire of liberty” expanding westward fundamentally depended on the legal fiction that European-derived nations held superior rights to the continent.

Jefferson’s complex relationship with Native Americans reflected this tension. While expressing admiration for certain aspects of Indigenous cultures and even conducting some of America’s earliest ethnographic work, he simultaneously advanced policies predicated on removal and assimilation. He viewed Native American societies as “savage” and in need of “civilization,” a perspective that directly stemmed from the religious and cultural precepts embedded in the Discovery Doctrine.

A Foundation for ‘Manifest Destiny’ and ‘American Exceptionalism’

The Discovery Doctrine laid the groundwork for Manifest Destiny, the 19th-century belief that American expansion across the continent was both inevitable and divinely ordained. This ideology, which gained prominence in the 1840s, built directly upon the doctrine’s premise that European-descended Americans had superior claims to the land.

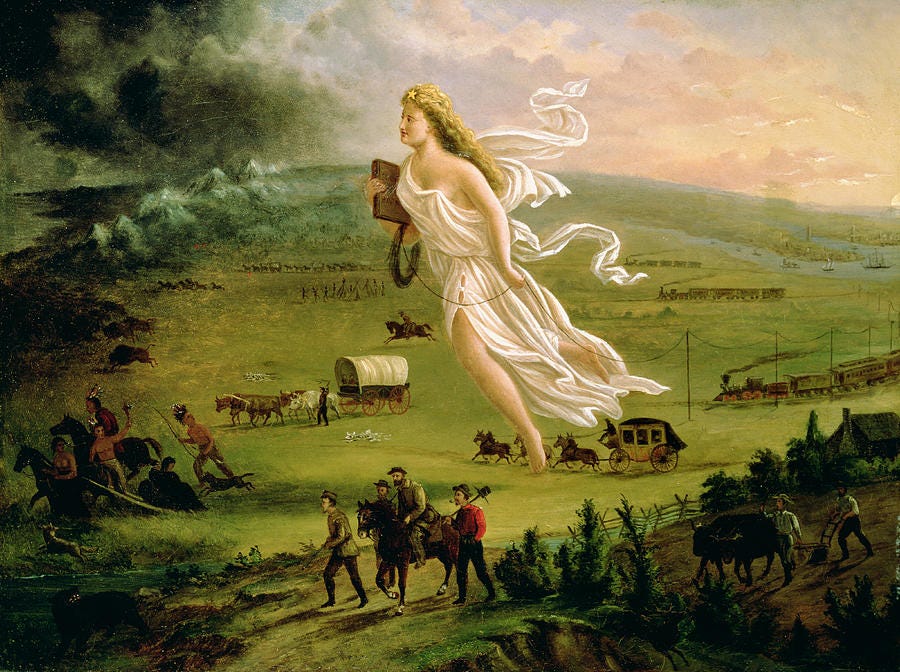

The concept of Manifest Destiny secularized the religious aspects of the Discovery Doctrine while maintaining its essential hierarchy. Rather than explicitly assert Christian superiority, it emphasized American cultural and political superiority, though with religious undertones. The famous 1872 painting “American Progress” by John Gast visually captured this ideology, depicting a floating female figure carrying a schoolbook and telegraph wire, bringing “civilization” westward while Indigenous peoples and wildlife flee before her.

Similarly, American Exceptionalism - the belief that the United States occupies a special place in world history due to its unique origins, political system, and supposedly divine favor - draws intellectual sustenance from the Discovery Doctrine. The notion that America has a special destiny or mission in the world echoes the doctrine’s assertion of European-Christian supremacy, merely transferring that mantle of superiority to the American experiment.

The Discovery Doctrine’s influence on these ideologies created a persistent pattern in American history: territorial expansion justified through claims of cultural, political, and religious superiority. This pattern shaped not only domestic policies regarding Native Americans but also America’s later approach to international relations, where elements of this exceptionalist thinking continued to influence foreign policy well into the 20th and 21st centuries.

Current Status

Despite widespread recognition of its problematic origins and effects, the Discovery Doctrine remains embedded in American law. The doctrine was most notably affirmed in the 1823 Supreme Court case Johnson v. McIntosh, where Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that Native Americans could not sell land to private citizens because their rights to the land had been diminished by European discovery. Marshall wrote that “discovery gave title to the government by whose subjects, or by whose authority, it was made, against all other European governments, which title might be consummated by possession.”

This ruling has never been explicitly overturned. In fact, the Supreme Court has referenced the doctrine in subsequent cases, including as recently as 2005 in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, where Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg cited the “Doctrine of Discovery” in a ruling against tribal land claims.

The doctrine’s persistent influence has drawn increasing criticism from Indigenous rights advocates, legal scholars, and international bodies. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has called for the repudiation of the Discovery Doctrine, describing it as “the shameful root of all the discrimination and marginalization Indigenous peoples face today.”

Some religious organizations have formally repudiated the doctrine, including the Episcopal Church in 2009 and the World Council of Churches in 2012. Various Christian denominations have issued apologies for their role in promoting the doctrine and its devastating consequences for Indigenous peoples.

At the government level, there have been some acknowledgments of the doctrine's harmful legacy. In 2009, the US Congress passed a resolution apologizing to Native Americans for “years of official depredations, ill-conceived policies, and the breaking of covenants,” though without specifically mentioning the Discovery Doctrine. In 2023, the Roman Curia of the Vatican formally repudiated the doctrine.

Despite these developments, the doctrine has not been formally rejected in American jurisprudence. It represents one of the clearest examples of how colonial-era legal principles continue to shape contemporary law and policy regarding Indigenous peoples in the United States.

The ongoing influence of the Discovery Doctrine on Western culture highlights the subtle and complex ways in which historical injustices remain codified in the social consciousness of Western societies - including attitudes toward legislation, formulation of domestic and foreign policy - presenting significant challenges for efforts toward reparations, reconciliation and decolonization in the 21st century.